When I came across Turbopuffer, a vector database built entirely on object storage, I got curious. Really curious. The architecture seemed almost too simple. Write-ahead logs on S3? Centroid-based indexes? Stateless query nodes? It felt like someone had taken all the "rules" of database design and just... ignored them.

I wanted to understand the tradeoffs myself. Not by reading more blog posts, but by actually building something. Also I broke up with my girlfriend, so I have nothing else to do.

We'll build a naive vector database on S3, inspired by Turbopuffer's architecture, using first principles and napkin math. We'll hit walls, make mistakes, and hopefully learn what design decisions we need to make.

The more interesting thing about this is, S3 is meant to be object storage, it's not that designed for database operations. We need to think about updates, deletes, managing indexes - how we store them, update them, and minimize roundtrips because every extra roundtrip is 200ms latency which your users will not like. So it's not that easy to just use S3 and turn it up to infinite scale.

I'm not a database expert. I'm not the hardcore database guy who tweets about LSM trees and drops random MySQL facts at parties. I'm just someone who likes tinkering with things to understand how they work.

This is a learning exercise. I'm building my own version of turbopuffer to really understand the trade offs, the gotchas, and why certain decisions were made. If you're looking for production-ready code or groundbreaking research, this isn't it. But if you want to follow along as I figure out how to build a vector database from first principles, you're in the right place.

What are we actually optimizing for? #

Why do we even want to build on S3, and why not in a traditional way or use top-of-the-shelf solutions like pgvector or other millions of solutions?

imagine you want to add semantic search to your app. Maybe 100 million vectors. You check pricing for existing vector databases, Pinecone, Qdrant, etc... $20k per month. Just for storage. That's insane.

Why so expensive? Because traditional vector databases assume you need everything in memory or on expensive replicated SSDs, and that's where a good scale solution built on top of S3 with smart caching really shows its worth.

That said, let's set some reasonable goals for what this thing should do:

- Doesn't bankrupt you - Should cost

$1500/month for a billion vectors, not $20k - Scales horizontally - Add more

namespaces without 10x-ing your costs - Handles writes properly - Real-time

inserts/deletes, no rebuilding entire indexes - Is fast enough - Not "fastest possible," but fast enough (

p95 under 500ms for 10k result searches)

Overview of architecture:

// Write path:

upsert() → write_to_wal() → return_immediately

// Background (async):

compactor_job() → read_wal_batch() → build_indexes() → write_indexed_clusters() -> delete_wal_files()

// Query path (hybrid):

query() → {

indexed_data: fast_cluster_lookup(), // ~10ms

unindexed_data: scan_recent_wal(), // ~200ms

merge_results()

}

Let's start with writing and dumping things, simple Write-Ahead Log (WAL) implementation:

On every write request, we store the incoming data in a WAL folder in the user-provided namespace. We use the sequence as WAL file names: namespace/WAL/0000000001.bin.

This is a brute-force approach, but it works.

But now we have another problem: you can easily make a mistake and override the file, and your data is now overwritten, which is really bad for a database.

For this, S3 provides us a good API: you can pass the precondition in the request header to perform conditional writes. So we can simply use if_non_match: * — if the same key already exists, it will give us a 412 status code that the precondition failed.

We also have another latency killer: when a user fires a query asking for results, we need to fetch WAL files. But S3 doesn't provide a way to fetch all files from a folder — you can only fetch a file, and for that you need to know the exact key name and bucket. S3 doesn't provide regex-based file fetching either.

The only way is to LIST all files using a paginator, then fetch them in parallel. Each LIST operation is ~200ms per page, and each GET is another ~200ms.

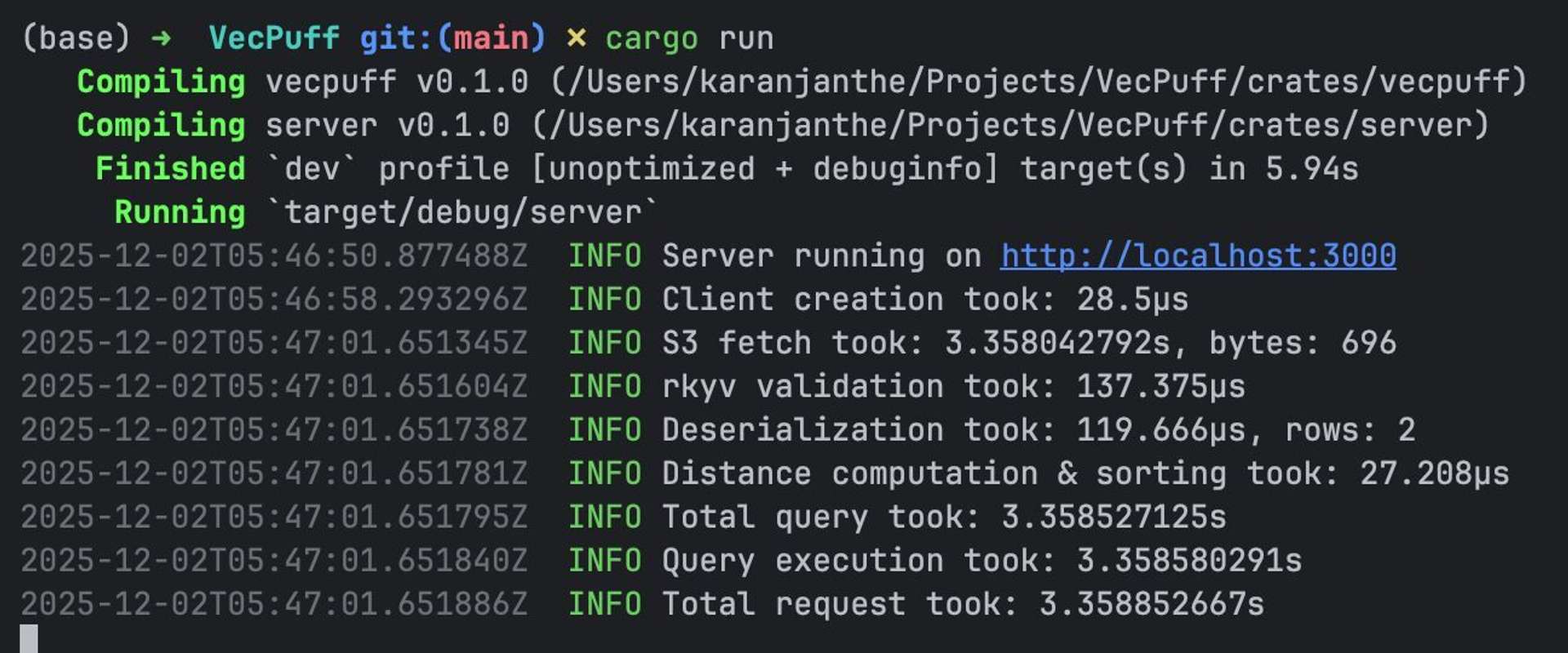

After pushing my crude basic version, I got my first benchmark result. 3 seconds per query. THREE SECONDS.

I was devastated. Therefore I started investigating...

Step 1: Physics Lesson (3000ms → 1000ms) #

I'm in Ahmedabad. Tigris servers are in us-east-1 (Virginia) despite choosing singapore.

- Speed of light round-trip:

~250ms TLS handshake (3 round trips): ~750ms- My naive

LIST operation: Another 300ms

I realized I was fighting physics, not code.

I could eliminate the expensive LIST operations. Instead of asking S3 "what WAL files exist?", I stored the file list in simple metadata.json and cache it, so my first cold query would be expensive but subsequent queries would be fast.

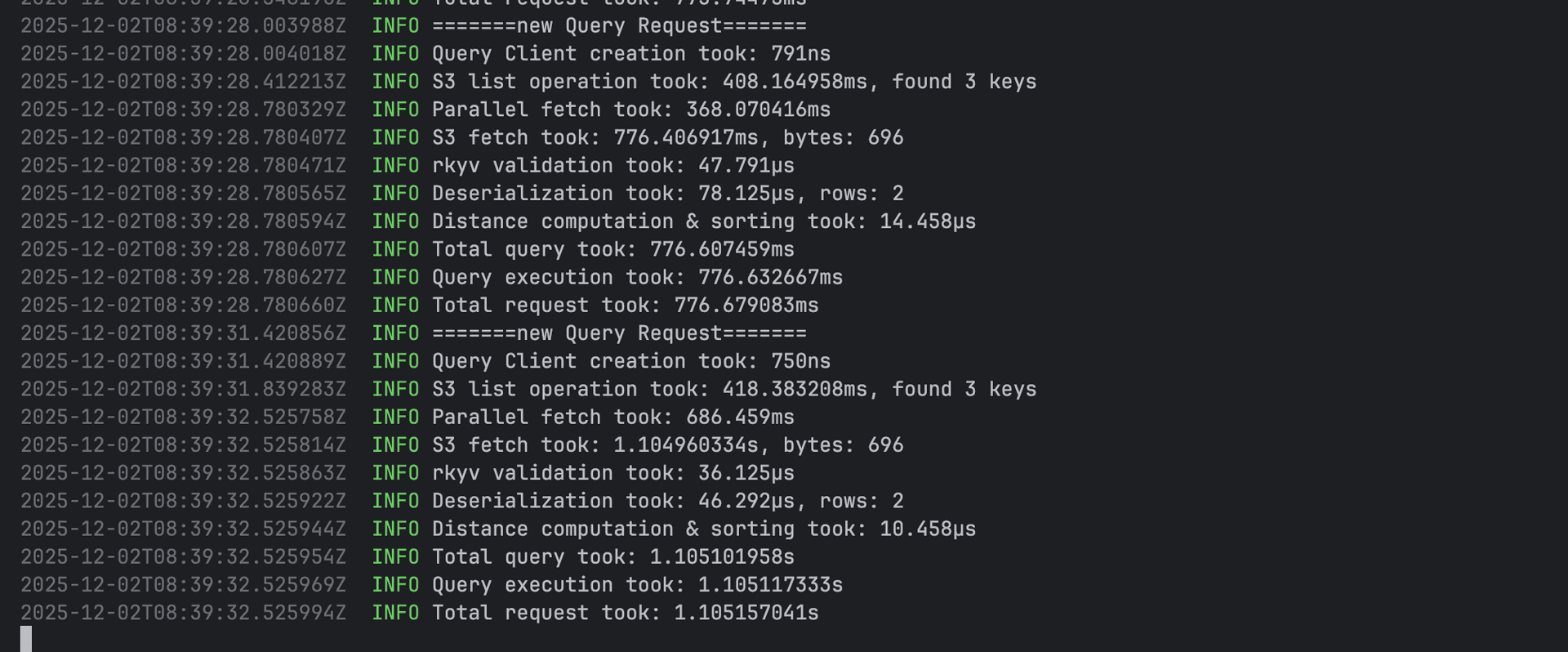

1000ms queries. Better, but still terrible.

In the above image, we are still using LIST operation, and I think it may have been some routing issue or something, because I was using Tigris blob storage and all other operations were in µs, despite them mentioning they are faster than S3. I wrote to them but didn't get proper followup.

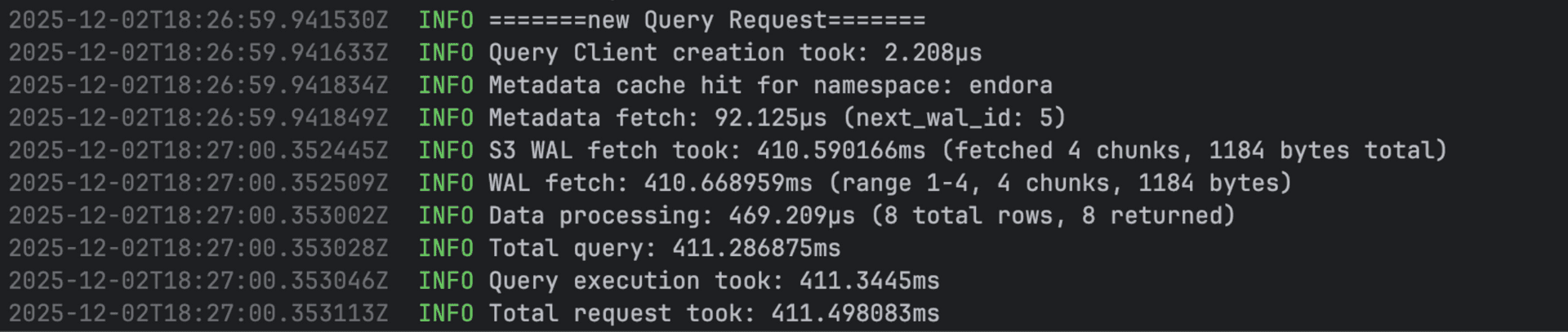

Every query was fetching metadata.json from S3. So why not cache it? I added a window LFU-based cache using moka:

// Window LFU eviction, max 1000 entries

static METADATA_CACHE: Cache<String, Metadata> = Cache::builder()

.build();

The cache uses a standard HashMap under the hood, the LFU algorithm will evict least-frequently-used entries once the limit is hit. At worst, you'll have 1000 entries (~1MB total memory for metadata). Memory isn't a concern here. In reality, if you ever have that many concurrent namespace accesses, your server would crash from in-memory vector buffers long before hitting metadata cache limits. That's a good problem to have.

I use proactive invalidation on writes to keep the cache fresh, letting the LFU algorithm handle eviction for less-frequently accessed namespaces and to be on safer side added max capacity of 1000.

Result: 400ms queries. Getting warmer.

Patch and Delete: The WAL Replay Story #

Since everything in our system is append-only (we can't update S3 objects in-place), how do we handle updates and deletes?

Answer: Write-Ahead Log (WAL) replay with tombstones.

#[derive(Archive, Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

pub enum WalRecord {

Upsert(Row),

Delete { id: DocumentId, timestamp: i64 },

Patch { id: DocumentId, attrs: HashMap<String, AttributeValue>, timestamp: i64 },

}

When you delete a vector, we don't actually delete anything. We write a tombstone record to the WAL:

// Delete operation

async fn delete(&self, namespace: &str, id: DocumentId) -> Result<()> {

let tombstone = WalRecord::Delete { id, timestamp: chrono::Utc::now().timestamp() };

self.write_to_wal(namespace, vec![tombstone]).await

}

Similarly, patches update attributes without rewriting the entire document:

// Patch operation

async fn patch(&self, namespace: &str, id: DocumentId, attrs: HashMap<String, AttributeValue>) -> Result<()> {

let patch = WalRecord::Patch { id, attrs, timestamp: chrono::Utc::now().timestamp() };

self.write_to_wal(namespace, vec![patch]).await

}

During query time, we replay the entire WAL to build the current state:

// WAL replay logic

fn replay_wal_with_tombstones(wal_chunks: &[Vec<u8>]) -> Result<(HashMap<DocumentId, Row>, HashMap<String, i64>)> {

let mut state = HashMap::new();

let mut deleted_ids = HashMap::new();

for chunk in wal_chunks {

let records: Vec<WalRecord> = rkyv::access(&chunk)?;

for record in records {

match record {

WalRecord::Upsert(row) => {

state.insert(row.id.clone(), row);

}

WalRecord::Delete { id, timestamp } => {

deleted_ids.insert(id.to_string(), timestamp);

state.remove(&id);

}

WalRecord::Patch { id, attrs, timestamp: _ } => {

if let Some(row) = state.get_mut(&id) {

for (k, v) in attrs {

row.attrs.insert(k, v);

}

}

}

}

}

}

Ok((state, deleted_ids))

}

The trade-off: Deletes are fast (just write a tombstone), but WAL replay gets slower as you accumulate more records. That's why we need compaction...

Obviously we can't store things in JSON format, serializing and deserializing JSON is painfully slow for our use case when dealing with millions of vectors!

I wanted to take advantage of zero-copy deserialization (read data directly without loading it entirely into memory first), and that's why I chose rkyv.

I also considered existing formats like Parquet, but here's why they don't work well for real-time vector search:

Parquet vs Rkyv: The CPU Battle #

Parquet (CPU Heavy)

Parquet is optimized for storage size using heavy compression and encoding (RLE, Snappy/Zstd):

Process: Download bytes → Allocate heap → Decompress → Decode → Construct structs

Result: CPU spends 50% of query time just preparing data before computing similarities

Rkyv (CPU Free)

Rkyv guarantees the data on disk is byte-for-byte identical to its representation in RAM:

Process: Download bytes → Cast pointer → Ready

Result: Data is ready the instant the network request finishes. CPU goes straight to SIMD vector math.

When you're fetching multi-MB posting lists from S3, this difference is massive. Zero allocations, zero decoding overhead, but at the same time debugging it is also an issue.

Write Collisions: The ULID Mistake #

Before going for any new optimization, I created a basic benchmark script in Python so I could test things properly instead of just guessing:

uv run vecpuff-bench latency \

--dataset-size 1000 \

--vector-dims 1536 \

--query-count 100 \

--warmup-queries 2 \

--batch-size 200

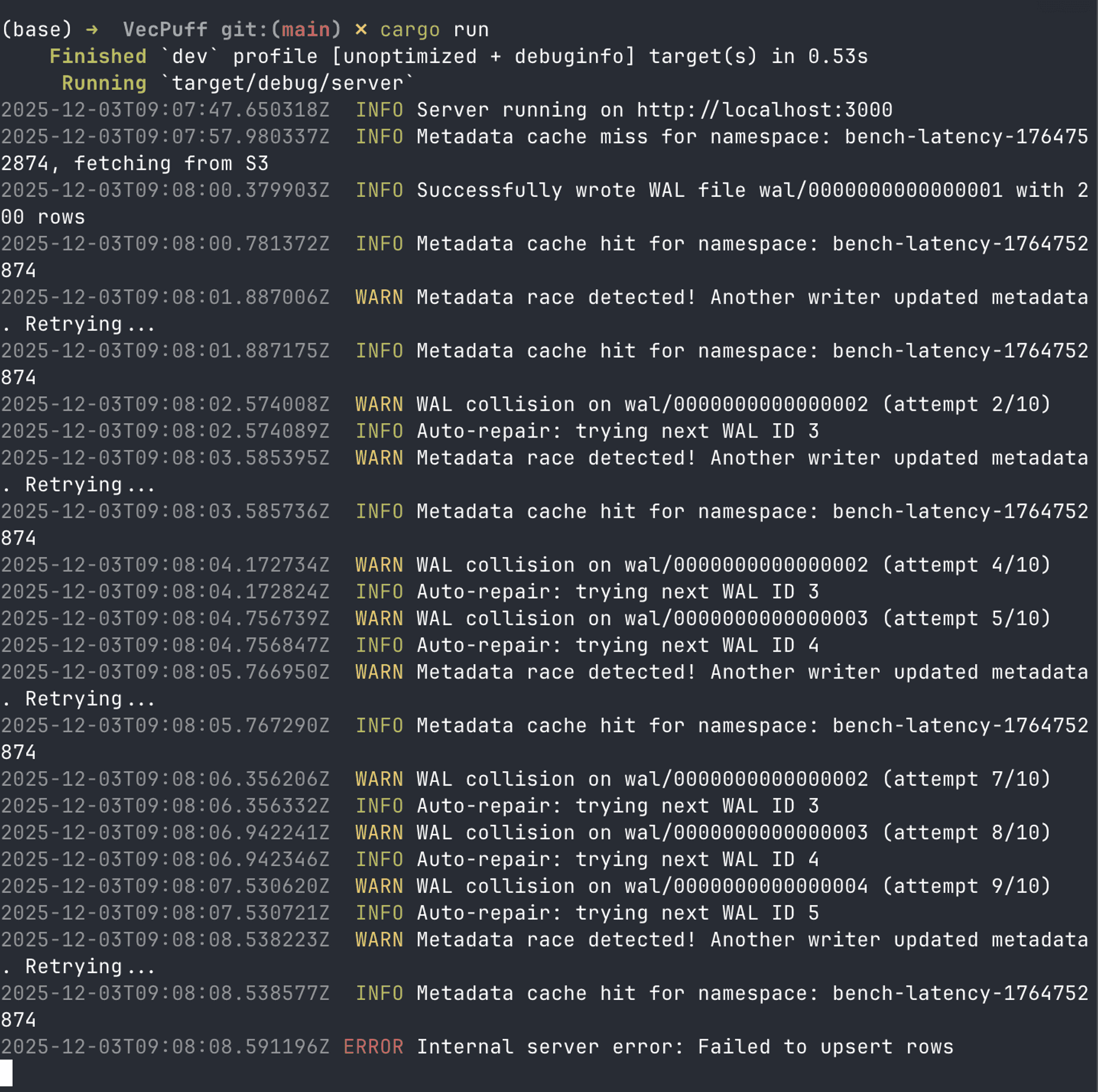

And immediately hit my metadata race condition (remember the collision problem I mentioned earlier):

Under concurrent load, my system was blowing up.

My initial thought was the sequential WAL approach is the main problem — we don't know what the next sequence is because multiple writers are trying to create files at the same time, and we needed to have sortable IDs for WAL files, otherwise Patch and Delete will not work.

We need IDs which are sortable and unique. I knew about ULID — they are 128-bit IDs, sortable and unique, and 26 characters long, so they are perfect for our use case. I implemented it in my code, it all worked like a charm, just needed to change the logic to store the WAL file names in metadata files.

Here I made a mistake that I realized later after completing the compaction and indexing logic: The problem wasn't the sequential WAL approach — it was having multiple concurrent writers trying to create files at the same time.

After a few days of debugging and arguing with LLMs about various approaches, I realized the solution:

Don't fix the collision - eliminate the writers!

Smart Batching: Single Writer Architecture #

Instead of multiple writers fighting over sequence numbers, funnel all writes through a single batcher:

// Wrong: Multiple writers = collision hell

API Request A → Write wal_00005.bin

API Request B → Write wal_00005.bin // COLLISION!

API Request C → Write wal_00005.bin // COLLISION!

// Right: Single writer + batching = no collisions

API Request A ──┐

API Request B ──┤─→ Batcher → Write wal_00005.bin (contains A,B,C)

API Request C ──┘

Scenario 1: Single Write (No Batching)

Time 0ms: Write arrives

Time 285ms: Immediately flush to S3, return success

Result: 285ms latency, no batching benefit

Scenario 2: Multiple Concurrent Writes (Batching)

Time 0ms: Write A arrives → Start batch

Time 50ms: Write B arrives → Add to same batch

Time 100ms: Write C arrives → Add to same batch

Time 285ms: Flush entire batch to S3 → All return success

Result: A=285ms, B=235ms, C=185ms latency

Scenario 3: High Frequency Writes

Time 0ms: Batch 1 (A,B,C) flushes → 285ms latency

Time 200ms: Write D arrives → Start new batch

Time 400ms: Write E arrives → Add to batch

Time 485ms: Flush batch 2 (D,E) → D=285ms, E=85ms

Even after understanding this, I ignored it because I thought this is not a good way - single writer architecture is not good. I liked the idea of batching, but not single writer, because when we have multiple nodes in different regions we need to have different writers. That was my intuition, so I just implemented batching with ULID-based IDs. But after a few days of thinking and arguing with LLMs about various approaches, I realized the solution, and I think this is how Turbopuffer also does this.

Routing is key here - all your requests go to the same node every time, using consistent hashing/hash ring.

So I could have stuck to the sequential WAL IDs approach!

Compaction and Indexing: #

After benchmarking, I had thousands of WAL records. Replaying them all was taking 200ms+ per query. Time for indexing.

Enter ANN based indexing:

Why everyone loves HNSW:

Hierarchical Navigable Small World graphs- Great for in-memory vector search

- Excellent recall and speed

Why HNSW sucks for our use case:

We are going for S3 in the first place to reduce the cost because of our scale. To make HNSW work for our use case, we need to load the entire index in memory — without it, updates and other operations will be too slow.

SPFresh is a good choice for our use case. Watch this video for more details — it uses centroid-based indexing which is good for our use case, and LIRE for updating the index without rebuilding the entire index. I want to go into detail and talk about how it does this, but it would make this blog post a little long, so you can watch the video for more details.

// SPFresh strategy

impl SPFreshIndex {

pub async fn query_ann_async(

&mut self,

query_vector: &[f32],

top_k: usize

) -> Result<Vec<(f32, Row)>> {

// 1. Find nearest centroids (in-memory, fast)

let nearest_centroids = self.find_nearest_centroids(query_vector, 3)?;

// 2. Fetch posting lists for those centroids (parallel S3 GETs)

let posting_lists = self.load_posting_lists(&nearest_centroids).await?;

// 3. Compute similarities and return top-k

self.compute_similarities(query_vector, &posting_lists, top_k)

}

}

The algorithm:

- Cluster vectors into

centroids during compaction - Store

posting lists for each centroid in S3 - Query time: Download

centroids (small), find nearest clusters, fetch posting lists (big)

Performance:

Real logs from my benchmarks after implementing SPFresh:

INFO Metadata fetch completed for namespace: vecpuff, WAL files: 0, unindexed_bytes: 0

INFO SPFresh timing - Load: 365.423958ms, Query: 6.045541ms

INFO QUERY PERFORMANCE BREAKDOWN for namespace=vecpuff, docs=10, top_k=10:

INFO TIMINGS: Total=744.565542ms | Metadata=361.259875ms | Filter=42ns | WAL=165.75µs (fetch=49.417µs, replay=115µs) | SPFresh=382.982042ms | Merge=2µs | Sort=21µs

INFO S3 PERFORMANCE: 3 round trips [s3:read:metadata/metadata.json, cache:read:index/spfresh_metadata_01KBYP7BP8WBDPD6SEBKVHP9ZY, cache:read:postings/posting_01KBYP6WGXYW1HGZND1AC3C79A]

SPFresh timing - Load: 365ms, Query: 6ms. Total query: ~800ms cold, ~30ms warm.

The compaction process merges WAL files into indexes:

// Compaction trigger

if metadata.wal_files.len() >= config.reindex_threshold_wal_count

|| metadata.unindexed_bytes >= config.reindex_threshold_bytes {

tracing::info!("Triggering Compaction for {namespace}");

tokio::spawn(async move {

compactor::trigger_compaction(&namespace);

});

}

This looks really simple but implementing it was not that simple - it took me some time to figure out how to do it properly.

The "Zombie WAL" Race Condition #

I encountered a race condition where compacted Write-Ahead Log (WAL) files were being "resurrected" in the metadata, effectively undoing the compaction process. This occurred due to a flawed merge strategy during optimistic concurrency control conflicts.

The Scenario

Our system has two concurrent processes updating a shared metadata.json file on S3:

- Compactor: Reads metadata, merges old WAL files (e.g., WAL_1, WAL_2, WAL_3) into an index, and updates metadata to remove the old WAL files.

- Ingester: Writes a new WAL file (e.g., WAL_4) and updates metadata to add it.

Both use Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC): read the file, modify it locally, and write it back only if the file hasn't changed (using ETags). If the write fails, they must retry.

The Bug: State Merging

The issue arose when the Ingester and Compactor conflicted:

- Initial State:

[WAL_1, WAL_2, WAL_3] - Ingester Start: Reads state, adds WAL_4. Local state:

[WAL_1, WAL_2, WAL_3, WAL_4]. - Compactor Exec: Compacting 1, 2, 3. Successfully updates S3 to

[INDEX_A]. - Ingester Conflict: Tries to write its local state but fails because S3 has changed.

- Flawed Retry Logic: The Ingester fetched the new remote state (

[INDEX_A]) but merged it with its local stale state. It unioned the file lists:- Remote:

[INDEX_A] - Local:

[WAL_1, WAL_2, WAL_3, WAL_4] - Result:

[INDEX_A, WAL_1, WAL_2, WAL_3, WAL_4]

The Ingester inadvertently wrote the old WAL files back into the metadata, creating "zombie WAL files."

The Fix: Delta Application

To fix this, we changed the retry logic from State Merging to Delta Application.

Instead of treating the local state as a source of truth to be preserved, we treat the Remote State (the one on S3) as the only truth. We then simply re-apply the specific operation (the "delta") to that fresh state.

Corrected Retry Logic:

- Ingester Conflict: Write fails.

- Fetch Remote: Get fresh state

[INDEX_A]. - Apply Delta: The only operation intended was "Add WAL_4".

- Remote:

[INDEX_A] - Delta:

+ WAL_4 - Result:

[INDEX_A, WAL_4]

This pattern applies to any OCC retry: always re-apply the delta to the fresh remote state, never merge stale local state.

Caching: The Secret Sauce #

Without caching, every query hits S3. With smart tiered caching, we go from 800ms to 30ms.

Tier 1: In-Memory (Hot)

WAL cache (~500MB), metadata cache (~100KB), and SPFresh index cache with sliding TTLs. Access resets the timer — hot namespaces stay cached. Proactive invalidation on writes ensures consistency.

Tier 2: Local NVMe (Warm)

Write-through file cache for all S3 objects. Try local cache first, fetch from S3 and cache locally on miss.

Tier 3: S3 Standard (Cold)

- Object storage,

50-200ms latency - Unlimited capacity,

$0.023/GB/month

Note: Metadata uses get_file_with_etag() which bypasses local file cache and goes directly to S3 (for ETag-based optimistic concurrency control).

Query → Memory → NVMe → S3

↓ ↓ ↓

~1ms ~10ms ~200ms

Real performance:

- Memory hit:

~30ms (95% of hot namespaces) - NVMe hit:

~50ms (90% of warm namespaces) - S3 miss:

~800ms (5% cold start)

Storage costs:

- Memory:

$2/GB (expensive, fast) - NVMe:

$0.10/GB (middle tier) - S3:

$0.023/GB (cheap, slow)

Cache Invalidation:

- WAL cache: Invalidated when files deleted during

compaction - Metadata cache: Invalidated on every write + after

compaction - SPFresh cache: Invalidated when new index built

- Local file cache: Deleted when S3 objects deleted

Sliding TTL keeps hot data cached, proactive invalidation ensures consistency

This architecture works at the speed of in-memory databases with the economics of object storage.

Conclusion #

The code is not production-ready and definitely not clean. It's open source under the name VecPuff. I broke up with my girlfriend, so this is mostly how I spent my time - building a database on object storage instead of processing feelings. Will clean it up later.

Building a database on S3 is possible, but it's not magic. You're trading latency for cost, complexity for scale. For the right workload, that trade is worth it. For most workloads, it's probably over-engineering.

Here's what I actually learned:

Physics beats algorithms. I spent days optimizing queries before realizing I was fighting the speed of light, not code. Geography matters more than cleverness.

S3 request costs will surprise you. Storage is $0.023/GB, but 1M GETs/day is $12/month. My first benchmarks were doing 50+ GETs per query. That math doesn't work at scale. Batching isn't optional.

Cache invalidation is harder than it looks. Even with ETags and optimistic concurrency, you'll hit edge cases. The zombie WAL bug happened because I merged stale local state with fresh remote state. Delta application fixed it, but I should have known better from the start.

Zero-copy actually matters. When you're fetching 10MB posting lists from S3, JSON deserialization becomes a bottleneck. Rkyv's zero-copy meant data was ready the instant the network request finished. CPU went straight to SIMD math instead of parsing. The difference was 50ms → 5ms for large fetches.

Race conditions will find you. The zombie WAL bug taught me that distributed systems have a way of exposing your assumptions. State merging seemed logical until it resurrected deleted files. Delta-based operations are the only safe retry pattern.

Embeddings are reversible. They're lossy compression — you can reconstruct the original data from embeddings. If you're storing embeddings in S3, encrypt them. Your vectors might leak more than you think.

Building a database to cope with a breakup: surprisingly therapeutic. Would recommend over doom-scrolling.

Further Reading #

If you want to understand the thinking behind turbopuffer, I highly recommend watching Simon's talk on Napkin Math. It's not specifically about turbopuffer, but it shows the first-principles thinking that makes systems like this possible. Before you architect anything, do the math. Understand your constraints. Know what's physically possible before you start coding.

It's one of those talks that changes how you approach engineering problems.

More resources:

Published

Subscribe for future blogs